|

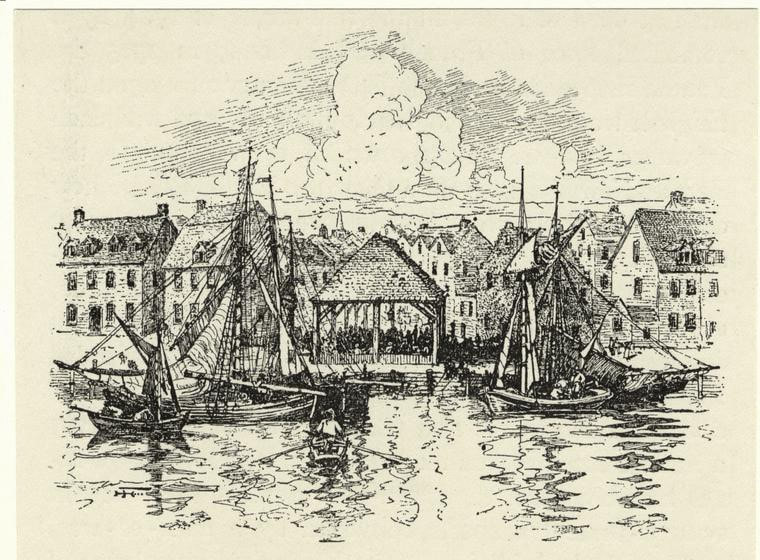

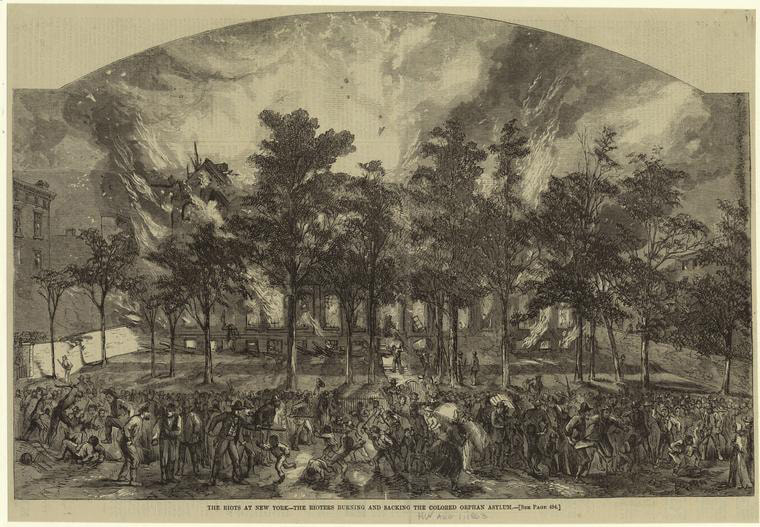

By Laurie Lewis Black people have lived in New York City from its inception. Even before then. Researchers have discovered that the first non-native long-term resident was Juan Rodriguez, whose mother was African. Rodriquez arrived on a Dutch ship from Santo Domingo in 1613. His crewmates soon returned to the Netherlands, but Rodriguez chose to remain here. The Dutch returned more than a decade later to establish the colony that would become New York, and soon they brought in the next Black residents: slaves from Africa and the Caribbean. When the English took over the colony, they continued to import slaves. By 1700, about 15 percent of the city’s population was Black, mostly slaves. In 1711, a slave market rose on Wall Street at the East River; it operated for more than 50 years. The Wall Street Slave Market It's the short, open-sided building in the center. (From the New York Public Library digital collection) By the mid-1700s, New York had more slaves than any other city in the country except Charleston, South Carolina. As in the South, some slaves here worked in the homes of their white owners, but most performed the hard manual labor necessary to build the thriving metropolis. New Yorkers often claimed to have welcoming attitudes toward Blacks, but reality told a different story. Consider the case of Peter Williams, a sexton at Wesley Chapel (later called the John Street Methodist Church; it is still active). The son of slaves, Williams feared that he might be sold to an unkind master, so the church purchased him. He repaid the price within two years, securing his freedom. But that didn’t make him equal in the congregation. Like the other Black worshippers, both slave and free, he had to sit in a separate section. In 1796, tired of the church’s discriminatory practices, Williams led a group that split off from Wesley Chapel to form an all-Black congregation. Northern states, including New York, began to pass legislation in the late 1700s to abolish slavery. But the laws usually did not go into effect immediately and did not apply universally. New York’s initial emancipation act, passed in 1799, freed people born after the first half of that year, but not until they became adults. A subsequent law granted freedom for slaves born earlier, but they remained slaves for ten years, until 1827. Abolition of slavery, in other words, was a promise that took decades to fulfill. Some free Blacks purchased land and built homes in areas remote from the population center in southern Manhattan, where racism often smoldered just under the surface. Seneca Village began in 1825 in an area that is now part of Central Park. By 1855, about 225 people, mostly but not exclusively Black, lived in Seneca Village. At that point, Weeksville, in what is now part of Crown Heights, Brooklyn (which was a separate city at the time) had more than twice as many residents as Seneca Village. Begun in 1838 as an enclave for free Blacks, Weeksville boasted the highest rate of home ownership among Black urban communities in America. That was important, because Black men had to own at least $250 in property to vote in the state. (Neither of these communities exist any longer. In 1857, the city took over Seneca Village to create Central Park. Weeksville gradually disappeared as Brooklyn developed around it, although remnants of a few buildings and oral history live on through the Weeksville Heritage Center.) Outside of these communities, Blacks in New York before the Civil War often lived in poverty and were constantly exposed to racism. Many resided in the notorious Manhattan slum known as Five Points or in undesirable streets in Greenwich Village like Minetta Lane, which was built over a brook and tended to flood during storms. Black men, women, and children in the white-ruled city lived in fear of such atrocities as being kidnapped and sent South into slavery. (A book to be published this fall, The Kidnapping Club by history professor Jonathan Daniel Wells, describes how this practice thrived in antebellum New York.) Animosity toward Blacks took a horrendous turn in 1863 during the Civil War Draft Riots. A federal conscription law created a draft lottery for male citizens. Because Blacks were not considered citizens, they were exempt. Other men could opt out by hiring a substitute or paying $300—about a year’s earnings for the average worker. In protest of the lottery, draft-eligible New Yorkers rioted for four days starting on July 13, targeting military and government buildings as well as Black people. The rioters destroyed Black homes and businesses and brutally attacked Black men and women. The Colored Orphan Asylum burned to the ground; fortunately, the children escaped unharmed. By the end of the riots, at least 100 people and probably many times that number were dead. Many historians consider the Draft Riots the worst civil disturbance in the United States. The Colored Orphan Asylum burning during the Civil War Draft Riots of 1863 It was located far outside the population center of Manhattan, on 43rd Street. (From the New York Public Library digital collection) The history of Blacks in early New York does not paint a shining example of the city. Despite the outward appearance of acceptance, Black residents often were subject to discrimination and violence. Second-class status was the hallmark of Black life in New York (as in other northern cities) through the Civil War era. Shared Causes, but... Later this summer, a statue of three nineteenth-century women will be unveiled on Central Park’s Mall. It will be a first; other statues in the park depict only fictional females. The women in the new sculpture are Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Sojourner Truth—all noted suffragists and abolitionists. Those political labels blur a dispute that developed in the rights movements in the post-Civil War period. Anthony and Stanton believed that a Constitutional amendment should give women the right to vote before or at the same time as Black citizens became eligible to vote. That viewpoint, sometimes expressed in racist language, lost. The Fifteenth Amendment, which secured voting privileges for Blacks, passed in 1870. That didn’t mean that Sojourner Truth, the only Black of the threesome, could vote. Fifty years elapsed before the Nineteenth Amendment guaranteed women the right to vote. More About New York If you would like to learn more about New York between issues of this newsletter, follow me on Twitter at @LLewisNYCfirsts. Many of my tweets celebrate the anniversaries of events that happened in New York before they occurred anywhere else. Tours Tours are suspended during the coronavirus pandemic. Comments are closed.

|

Archives

April 2024

|