|

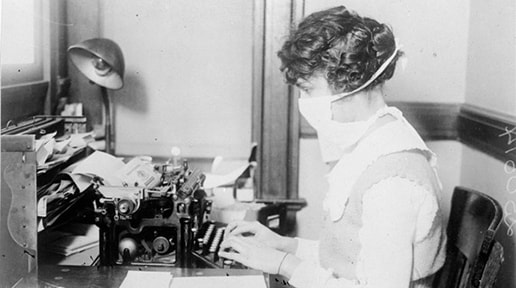

By Alan R. Cohen The world saw a lot of death in 1918. The “Great War,” which lasted until November 11, claimed an estimated nine million military personnel and an additional seven million civilians. The influenza pandemic of 1918–19, misnamed the Spanish flu, was far deadlier. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that the 1918 influenza pandemic infected about 500 million people worldwide and killed 50 million or more, including about 675,000 in the United States. The flu was especially deadly in three groups: children younger than 5 years of age, adults 65 years and older, and—unusual for influenza—20-40-year-olds; in fact, the flu was most deadly in these younger adults. This was a new type of flu, and people had no natural immunity; it was the first instance of the now-familiar H1N1 variety. The virus spread rapidly throughout a world that lacked vaccines or effective pharmaceutical remedies. The only ways to contain the outbreak were through quarantine, disinfectants, crowd control, and good public hygiene. Face masks were a public health measure to prevent spread of influenza Cosmopolitan cities like New York are ideal places to spread contagious diseases. With large numbers of immigrants and travelers, as well as groups congregating in transportation, schools, offices, factories, and theaters, the conditions are ideal . . . from a microbe’s perspective. In many cities in Europe and the United States, large numbers of people became infected with and died from the Spanish flu. New York City, however, defied expectations. The city had relatively few flu cases compared with other urban centers, and “only” about 30,000 people died, a small fraction of the total death toll in this country. It may have just been luck, or it could be thanks to one man, Dr. Royal S. Copeland (1868-1938). When he was appointed New York City’s health commissioner in May 1918, Copeland’s first task was to combat venereal diseases being spread by soldiers passing through the city upon their return from war. He also led a vaccination campaign to reduce childhood mortality from typhus. Then in August, word reached New York of an influenza epidemic with a high mortality rate affecting Spain. Actually, the flu was spreading throughout Europe, but wartime press blackouts suppressed information about the disease except in neutral Spain; hence the misnomer. The flu came to New York City in waves over about a year’s time, with the highest death toll from about mid-September to mid-November 1918. Copeland quarantined infected seamen arriving in the city’s busy port. But he was generally loath to implement the more restrictive measures that other cities instituted, such as closing schools and discouraging workers from taking mass transit at rush hours. Copeland believed children were safer in schools than at home. He did close poorly ventilated theaters but allowed large ones to remain open. Insisting that the life of the city must go on, Copeland suggested that businesses stagger their work hours to reduce rush-hour congestion on trains. He relied on basic in-home and hospital-based nursing care and public health education, emphasizing common-sense measures such as covering sneezes, not spitting in public, and keeping family members with the flu in a separate room. The pandemic passed without a full understanding of what had caused so many deaths worldwide or how to prevent future outbreaks. Nobody knew whether it was just luck or Dr. Copeland’s steady hand as health commissioner that enabled New York to fare so well compared with other large cities. Germ City The 1918 influenza pandemic is but one contagion featured in an exhibition at the Museum of the City of New York called Germ City: Microbes and the Metropolis. With support from Wellcome, a charitable trust dedicated to promoting medical knowledge and world health, the museum and institutions in Geneva and Hong Kong are focusing on cities as centers for the migration and dissemination of disease-causing microbes and on public health efforts to cure epidemics. The two-gallery show runs until April 28, 2019. It explores how New York City has coped with everything from now-conquered diseases like smallpox to epidemics that are still with us, like Ebola virus. The Most Germ-Covered Surfaces in New York City Men’s Health magazine commissioned a quick—and surely unscientific—“study” in October 2017 to find out which NYC surfaces were the most germ ridden. The worst offenders and their germ count:

Other news organizations—the Wall Street Journal in 2009 and The New York Times on September 5, 2018—found different and far dirtier places, microbially speaking. For example, the inside of men’s wallets is germ heaven. Airport security trays are dirtier than most bathroom surfaces, likely because of the shoes placed in them. So what is a person to do? Experts say you should stop worrying about germs and just use common sense. Wash your hands often, and cover your sneezes. And when you visit public places like the Germ City exhibition at the Museum of the City of New York, try to avoid the door handles! October Tours Most Take a Walk New York tours cover 1 to 2 miles, last 2 to 2½ hours, and cost $25 per person. Advance registration is required. To register and to learn the meeting place, email the guide ([email protected] or [email protected]). Please arrive a little before the start time. Tours are cancelled if nobody has registered or if the weather is extreme; if in doubt, call or text Laurie (917-306-2868) or Alan (917-363-4292). Greenwich Village: In the Footsteps of Writers Many writers and other creative people have called Greenwich Village home. On this tour, you’ll meander through charming Village streets and peek into hidden cul-de-sacs as you learn where some famous writers—including Edna St. Vincent Millay, e.e. cummings, and Edward Albee—lived and fraternized with other creative types. Maybe the Village aura will spark your own creativity! Laurie gives this tour on Monday, October 8, at 1 PM. To reserve a place and to learn the meeting location, email her at [email protected]. Fort Tryon Park The high ground in Upper Manhattan that appealed to the new American army for a defensive fort when the country was young later attracted millionaires who wanted to build castles on the Hudson. On this tour, we'll walk from the site of Fort Washington to Fort Tryon Park, exploring vestiges of a Gilded Age estate. We'll take in the Heather Garden and the park's extraordinary Hudson River views. You'll hear about a fearless woman who was a good shot with a cannon, a self-indulgent tycoon, and a generous Rockefeller. We'll end at the Cloisters Museum, which you may want to visit on your own. Alan offers this 90-minute tour on Wednesday, October 17, at 11 AM. Email him ([email protected]) to reserve a space and to learn the meeting location. Green Spaces and Great Places on 42nd Street Walking from Bryant Park all the way to the East River, you'll discover parks among famous Midtown buildings. Learn why so many "pocket parks" occupy prime Manhattan real estate. Make a brief visit to several iconic buildings, including the public library, Grand Central, and the Chrysler Building. End by discovering Tudor City, a residential enclave that offers both green spaces and interesting architecture. Laurie gives this tour on Thursday, October 18, at 2 PM. To reserve a place and to learn the meeting location, email her at [email protected]. Public Art of Lower Manhattan You don’t need to go to a museum to see great art. This interactive tour includes some of the most interesting and varied art in New York City. The artworks are as old as the doors of Trinity Church and as new as the SeaGlass Carousel. Alan gives this tour on Saturday, October 20, at 10 AM. Email him ([email protected]) to reserve your place and to learn the meeting location. Central Park: Marvels of the Northern Half The northern end of Central Park features some of the city's most surprising landscapes and is the best place for fall foliage in all of Manhattan. Visit the Pool, which should be at its colorful peak; enjoy a hike through the woods; and end at New York's own Secret Garden, which will be glorious with Korean chrysanthemums at this time of the year. Join Laurie to enjoy fall foliage and flowers in the northern half of Central Park on Sunday, October 28, at 2 PM. Please email her ([email protected]) to register and to learn the meeting location. Central Park: Highlights of the Southern Half In the popular southern half of Central Park, you’ll recognize some of the most filmed and photographed sights in New York, including Strawberry Fields, the Sheep Meadow, and Bethesda Terrace. Enjoy the changing season with colorful foliage (it's not totally predictable, but it's usually good at this time). Join Alan on Wednesday, October 31, at 10 AM to take a walk through southern Central Park. Please email him ([email protected]) to reserve a space and to learn the meeting location. October Tours

|

Archives

April 2024

|