|

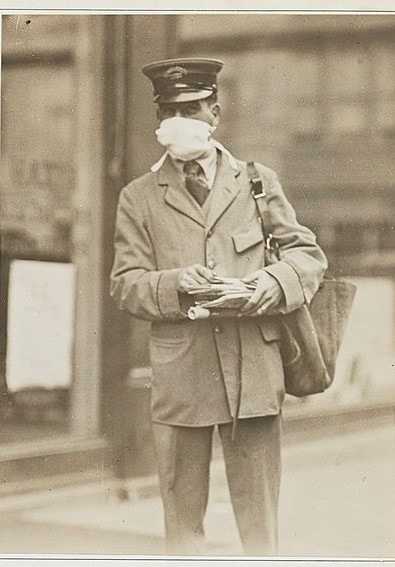

By Laurie Lewis With the ongoing battle against coronavirus, we are switching, at least for now, to a quarterly timetable for our newsletter. We'll still present stories about New York, but we won't be listing any walking tours. When we are allowed to give small-group tours again, we'll be happy to prepare a private or custom tour for you. As we continue to live with the coronavirus pandemic, patterns emerge that recall New York City’s past experiences. Epidemics were common in New York history. We’ve written about them in past issues (August 2016 and October 2018 ). Now we revisit them, looking for parallels with the current COVID-19 pandemic. A letter carrier during the 1918 influenza pandemic. Masks were part of everyday attire then, as they are today. When the United States was young, epidemics swept through the major cities. From 1795 to 1803, New York experienced its first epidemic, yellow fever, which took more than 800 lives. Like the present COVID-19 pandemic, the disease first arrived with travelers, in that case on ships coming from Philadelphia, where yellow fever was rampant. The extent of the yellow fever outbreak was little publicized, for fear that New Yorkers would panic and business would suffer. Sound familiar? Yellow fever again reached epidemic levels in 1805 and 1822. Neither bout was as deadly as the first, mainly because of practices familiar in the spring of 2020: quarantine, increased hygiene, and social distancing. The New York City Board of Health, formed specifically to combat the spread of yellow fever, evacuated the disease-infested districts, quarantining patients and providing food and shelter for other residents while the areas were cleaned. During the 1822 epidemic, wealthier residents decided to separate themselves, moving north to a previously unsettled area of the city, Greenwich Village—an early example of voluntary social distancing to prevent illness. The first smallpox epidemic was in 1804. Another smallpox epidemic occurred twenty years later, and major outbreaks resurfaced sporadically until the early twentieth century. Sometimes New Yorkers endured typhoid epidemics in the same year. Later, it was discovered that this disease could be spread by asymptomatic carriers—just like COVID-19—such as the infamous Typhoid Mary. The deadliest of all the recurring epidemics was cholera. New York’s first cholera epidemic, in 1832, killed more than 3,500 residents. The 1849 epidemic was even deadlier, taking more than 5,000 lives. The Board of Health swung into action, setting up makeshift hospitals—where have we seen that recently?—cleaning the streets of manure, and ridding them of pigs, which were thought to spread the disease. Improved sanitation made a difference. The death toll in the last cholera epidemic, in 1866, was about 1,100. Just as New York has been the epicenter of COVID-19 in the United States, it was the epicenter of the polio epidemic that began in 1916. The paralyzing disease spread throughout the country and was prevalent until the 1950s, when safe and effective vaccines became available. As their breathing muscles became paralyzed, patients often had to use an early type of ventilator called an iron lung. Like the ventilators used in treatment of COVID-19, iron lungs were expensive, and the need for them often exceeded the supply. The outbreak most often likened to the current coronavirus pandemic is the 1918 influenza pandemic. Like some outbreaks of the past and present, it began here when infected travelers arrived on American soil. Influenza came in three waves between August 1918 and February 1919, killing about 30,000 New Yorkers. As terrible as that number is, influenza did not take out as large a percentage of the population in New York as in other big cities, like Boston and Philadelphia, because of decisive action by the Board of Health. The measures included ones seen again in 2020: a public health education campaign to urge New Yorkers to cover their nose and mouth when sneezing and coughing, wearing of face masks, and quarantine of patients at home or in hospitals. Surveillance to get an accurate count of cases was as important in 1918 as it is today. Whereas Governor Cuomo ordered a “pause” to control the spread of coronavirus, schools and most businesses remained open a century ago during the influenza outbreak, although working hours were staggered to reduce congestion on public transportation—a problem then as now in normal times. Testing and contact tracing are keys to moving beyond the coronavirus “pause.” That is nothing new. Other epidemics, especially HIV, have established modern systems for testing and tracing. On the down side, the long and as yet unsuccessful search for an HIV vaccine, even with twenty-first century knowledge and technology, cautions that quick development of a vaccine to prevent coronavirus illness might not become a reality. Having dealt with epidemics for 225 years, New York City—in fact, the entire nation—already has much experience that will see us through the coronavirus crisis. History has taught us that what happens elsewhere can happen here, that a distant local epidemic can rapidly become a global pandemic. An outbreak is not an isolated event, and it may not be a one-time occurrence; epidemics can drag on for years or recur in waves. Therefore, the health care system and government bodies that respond to emergencies must be prepared. Prompt and decisive action, led by the government and requiring cooperation by all residents, can alter the course of the outbreak and reduce the number of cases and deaths. We’ve seen that in the past, and we’re seeing it now in New York. We’ve gotten through previous epidemics, and we’ll get through this one too. Life won’t be exactly the same afterward. It might actually be better. After all, if pigs hadn’t been banned from New York City streets after the cholera outbreaks, just think how noisy, dirty, and smelly our city would be. A New Venture A personal message from Laurie Lewis The coronavirus “pause” has been a good time to start and complete major projects. During this time, I finished the book I have been writing for the past three years, which I’m tentatively calling NYC Firsts: How New York Led the Nation and Even the World. I was excited to secure an agent last month. He tells me that I need a social media presence to interest publishers, so I have started a Twitter account, @LLewisNYCfirsts. Most of my tweets will be related to the book and will be in the form of a two-part trivia quiz. For example, my tweet on May 9 was “Tomorrow is the seventh anniversary of a tasty New York City original. Do you know what it is?” The next day I revealed the answer: the cronut. I would much rather be spending time taking a walk in New York than sitting in front of a screen. But times being what they are, long exploratory walks, especially in the company of others, are out of the question. The Twitter plan is actually a great way for people who love New York and its history to learn about the city while staying safely indoors. So please follow me at @LLewisNYCfirsts, and enjoy playing the trivia game. No Social Distancing! Two ducks and many turtles enjoy Central Park on a recent spring day.

Wish you were a turtle and didn't have to worry about COVID-19? |

Archives

April 2024

|