|

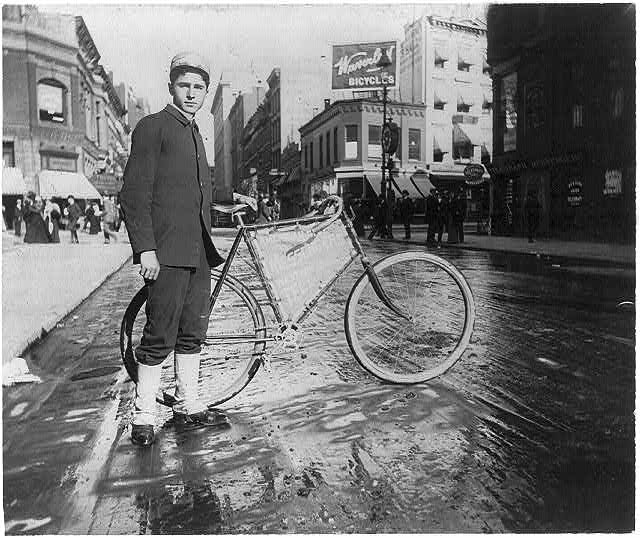

By Laurie Lewis The bicycle was a craze among men of means in the late 1860s until nearly the end of that century. Like most new toys, it was too expensive for working-class families, who could barely keep food on the table and who had little time for leisure activity. As for women, the mores and clothing of the Victorian era initially kept them off the bicycle. The early cyclists wanted to spin their wheels in newly developed Central Park. “No!” said the authorities, who viewed bicycles as a menace to other park visitors. It would be two decades before cyclists, who fought vigorously for the right to ride, received permission to pedal in Central and Prospect Parks, provided they had a license from the Parks Department, belonged to a cycling club, and refrained from speeding. Biking in Central Park 1895, Strohmeyer & Wyman By then, cycling was more egalitarian and not just for recreation. When they had become bored with their two-wheeled toys, some early adopters gave away their bikes or sold them at a steep discount. With bikes of their own, middle-class men and working-class boys, who had to help support the family, sometimes used the vehicle for work. Bicycle messengers whizzed through the streets, fulfilling a need essential to business in fast-paced New York City until recently, when email enabled quick—and weather-proof—document delivery. Bike messengers still exist, but the main bike deliveries today are restaurant meals for New Yorkers who want to eat at home without cooking. Messenger Boy and Bike c 1896, Alice Austen Leaders of the first wave of women’s liberation in the late nineteenth century promoted not only the right of women to vote but the right for them to be out in public without an escort and to engage in activities such as biking. Susan B. Anthony observed that the bicycle “has done more to emancipate women than anything else in the world. It gives women a feeling of freedom and self-reliance.” One difficulty, however, was the street-length, bulky dress of the times. Libby Smith Miller, cousin of suffragist Elizabeth Cady Stanton, modified the full-skirted dress to create loose pants gathered near the ankles, which made biking easier. Another advocate of women’s rights, Amelia Bloomer, touted the garment, and her name became an eponym. As more and more people mounted bicycles, the city leaders recognized a need for pathways devoted to the pastime. In 1894, the first dedicated bike lane in America opened on Ocean Parkway in Brooklyn. Created by dividing the pedestrian pathway designed three decades earlier by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, the masterminds behind both Central Park and Prospect Park, the bike path stretched 5.5 miles from the latter greenspace to Coney Island. Soon other bike paths opened in the Bronx along Pelham Parkway and in northern Manhattan along Riverside Drive. Bike Lane near Grant's Tomb in Manhattan c. 1898, W. C. Harris Meanwhile, the well-to-do were enjoying a new wheeled toy: the automobile. From the earliest days, cars and bikes did not always mix well on city streets. The first car-versus-bike accident in the country occurred on May 30, 1896, when several cars were participating in a “horseless wagon race.” Cyclist Ebeling Thomas must not have been aware of the contest, because he was pedaling in the opposite direction along Broadway at the very moment one of the drivers lost control of his car, hitting the biker and breaking his leg. The New York Times article reporting the incident also described the arrest of five speeding cyclists on the same day in other parts of the city—proof that both car drivers and cyclists sometimes behaved recklessly. In the early twentieth century, as cars became more popular and the subway system offered quick and affordable transportation, bicycles gathered dust and rust in New York City. They came out of storage during the Depression, providing a cheap alternative for getting around. In recent years, bicycles have become ubiquitous, especially the blue ones of the Citibike bike-share system. More than 800,000 New Yorkers bike regularly, and almost 52,000 commute to work by bike, often pedaling on the 100-plus miles of protected bike lanes. Bikes and larger vehicles continue to be as uncomfortable together on the city streets as they were on that day in 1896 when the first accident occurred. As of late September, 21 New York cyclists have died this year in accidents—more than twice as many as in all of 2018. Fifteen of those accidents occurred in Brooklyn, and most involved vans or trucks. Often the driver of the larger vehicle was at fault, but sometimes the biker failed to act cautiously. When it comes to sharing the road, little seems to have changed in more than 120 years. Museum Show on Bicycling If you hurry, you can still catch an exhibition at the Museum of the City of New York called Cycling in the City. The small but comprehensive show, which explores many points described in this article, runs through October 14. October Tours Most Take a Walk New York tours cover 1 to 2 miles, last 2 to 2½ hours, and cost $25 per person. Advance registration is required. To register and to learn the meeting place, email the guide ([email protected] or [email protected]). Please arrive a little before the start time. Tours are cancelled if nobody has registered or if the weather is extreme; if in doubt, call or text Laurie (917-306-2868) or Alan (917-363-4292). Fort Tryon Park The high ground in Upper Manhattan that appealed to the new American army for a defensive fort later attracted millionaires who wanted to build castles on the Hudson. We’ll walk from the site of Fort Washington to Fort Tryon Park, exploring vestiges of a Gilded Age estate. We’ll take in the Heather Garden and the park’s extraordinary Hudson River views. You’ll hear about a fearless woman who was a good shot with a cannon, a self-indulgent tycoon, and a very generous Rockefeller. We’ll end at the Cloisters Museum, which you may want to visit on your own. Alan offers this tour on Wednesday, October 2, at 10 AM. Email him ([email protected]) to reserve your spot and to learn the meeting location. Central Park: Highlights of the Southern Half In the popular southern half of Central Park, you’ll recognize some of the most filmed and photographed sights in New York, including Strawberry Fields, the Sheep Meadow, and Bethesda Terrace. An added treat this month is the changing fall foliage. Take a walk through the southern half of Central Park on Friday, October 11, at 1 PM. Please email the guide ([email protected]) to register and to learn the meeting location. Central Park: Marvels of the Northern Half One of the best places for fall foliage in Manhattan is the northern half of Central Park. Colors usually peak here a bit later than in the southern end, around the end of October. Even without the brilliant colors, this part of the park offers beautiful and surprising landscapes, including a wooded trail. At the end of the walk, Conservatory Garden welcomes with a gorgeous seasonal display of Korean chrysanthemums. We offer the tour twice this month. Join Laurie on Friday, October 25, at 1 PM or Alan on Wednesday, October 30, at 11 AM to take a walk through the northern end of Central Park when it is at its best. Please email the guide ([email protected] or [email protected]) to reserve your place and to learn the meeting location. October Tours

Comments are closed.

|

Archives

April 2024

|