|

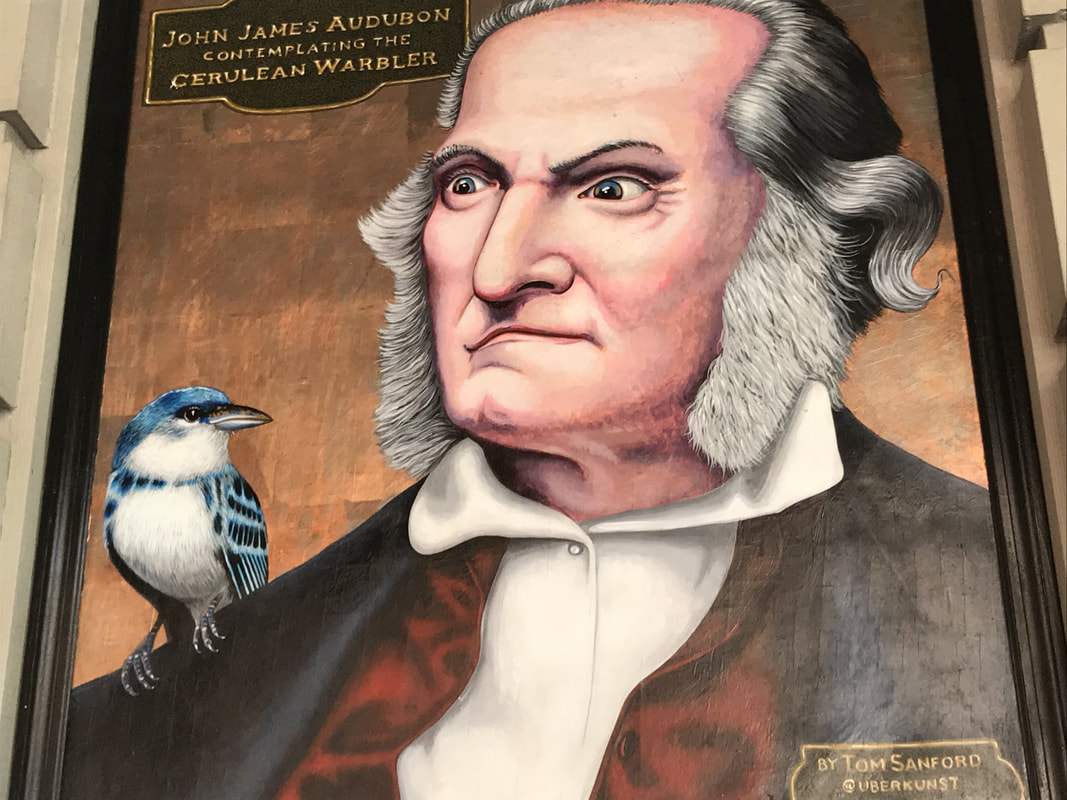

by Deborah Harley I decided to take a walk through Central Park’s North Woods the other day. I knew the Central Park Conservancy had completed a renovation of the area and was curious to observe the results. My reaction was “Wow!” If you haven’t been there lately, you are overlooking what I feel is the most spectacular landscape of the park. For one, the Conservancy has widened the Loch, the rivulet that runs through the woods, and restored it nearer to the size that Olmsted and Vaux had envisioned. It had dwindled to a thin stream over the decades. The Conservancy has also added natural paths that allow you to wander closer to the water and deeper into the woods for a more immersive experience. The North Woods is a unique landscape in the park, and Olmsted and Vaux designed it with a particular purpose in mind. During the mid-19th century, several influential cultural movements were introducing some radically unfamiliar ideas into the American consciousness. These included a new emphasis on the value of each person, a more profound appreciation of nature, and an increased ethical awareness. It was the time of the Romantics. Central Park was a product of these times, and its builders incorporated these new values and ideals into its design and construction. As the first built public park in the United States, everyone – whether rich or poor – was welcome. Nevertheless, the lower classes were the key beneficiaries of the park’s underlying egalitarian philosophy. For example, Vaux and Olmsted designed the North Woods to resemble the Adirondacks in upstate New York. As wilderness country, the Adirondacks became a popular destination for the wealthy seeking to escape the city. The upper class could travel there whenever they wanted, because they had the time and the means. The lower classes, however, had neither – especially considering they had only one day a week off, if they were lucky. Their lives were limited to the crowded confines of Manhattan, living and laboring under appalling conditions. Therefore, Vaux and Olmsted provided the lower classes with their own Adirondacks. Now even the poorest New Yorkers could experience nature – some for the first time in their lives. Central Park offered them a chance to walk through the woods, to breathe healthy fresh air, and to enjoy all the benefits that nature had to offer. For the Romantics, those benefits meant nothing less than a complete revitalization of one’s body, soul, and spirit. Think about this. Central Park was not built for the wealthy. It wasn’t built to make someone rich, inflate an ego, or build a reputation. It was built for all New Yorkers to enjoy, and through that experience become happier and healthier. This was a radical idea. How lucky we are that we can still experience this in the same way as New Yorkers did 150 years ago. Do yourself a favor. Take a walk in the North Woods and be refreshed. Come on our tour Central Park: Marvels of the Northern Half. We offer it often on our public tour schedule, or contact us to book a custom tour that fits your own schedule. by Alan R. Cohen My awareness of the Audubon Mural Project grew from an accidental encounter with what is now my favorite piece. As I was preparing a tour of Lower Washington Heights that would end at the Morris-Jumel Mansion, I was looking for the most interesting route and noticed a brightly colored facade in the distance. From afar, I could see it was iridescent with shades of blue and purple, but I had no clue what it was. When I approached the mystery, I was delighted to find Tri-colored Heron, a nearly five-story-high depiction of three herons competing for food. At the bottom on the piece was stenciled audubonmuralproject.org and the artist’s name, Iena Cruz. Tri-Colored Heron, by Iena Cruz The fun of being a tour guide includes the endless opportunities to learn more about the city and to pursue multiple, divergent, and interesting paths. Tri-colored Heron gave me one such path to follow. Upon visiting the project website, I realized that two of the murals on my M4 bus ride north to my apartment in Washington Heights are part of the project. As the bus goes north on Broadway at 155th Street (just past Trinity Cemetery), you can see the four-story-high Fish Crow, with splashes of yellow and orange against a terra-cotta background, on the south-facing side of an apartment building just past the gas station. Fish Crow, by Hitnes If you look to the east as the bus approaches the same intersection, you see another mural. This magnificent piece depicts the Swallow-tailed Kite and twelve additional bird species painted within the outline of the kite. Swallow-tailed Kite and Others, by Lunar New Year Now that I was officially obsessed with the art, I had to find out more. I learned that the project serves two major purposes: to call attention to endangered birds while simultaneously beautifying the neighborhood. The National Audubon Society has long been concerned with environmental threats to bird populations. Data published in 2014 revealed that at the current pace of climate change, 314 of the 588 North American bird species studied face changes to their natural habitat so major that if the species cannot adapt, they would decline significantly or possibly face extinction by 2080. Detailed reports from the scientists and an executive summary are available on the Society’s website (http://climate.audubon.org). The National Audubon Society wanted to find ways to sound the alarm and spur action. Around the same time, a native of Washington Heights, art collector and gallery owner Avi Gitler, was determined to bring art to Upper Manhattan. Realizing that there were no serious art galleries north of 125th Street, Gitler decided to open his own gallery on Broadway between 149th and 150th Streets. The space is a relatively small storefront, easily missed by the casual passerby. To call attention to his gallery, Gitler thought that murals on a roll-down gate might do the trick. In cooperation with his landlord, Gitler began with two adjoining stores. Given that his new gallery was a stone’s throw from John James Audubon’s former estate and Audubon’s final resting place in Trinity Cemetery, birds seemed a fitting subject for those first murals. An artist Gitler recruited, Tom Sanford, connected him with Mark Jannot, an executive of the Audubon Society. John James Audubon Contemplating the Cerulean Warbler, by Tom Sanford Through this serendipitous chain of events, the mural project was born. Gitler is the curator of the art. Artists from all over the world, including many locals who want a little publicity, apply to paint one or more of the endangered birds. As of this writing, more than 82 of the 312 endangered birds have been painted. Other birds are being added as permission and funding allow. Through Gitler, the Audubon Mural Project provides the funding. The costs for the smaller projects, which often are completed in one evening, are just for the paint and maybe a small honorarium to the artist. The larger projects—those on the sides of a building or sometimes multiple buildings—can take a week to complete and require the rental of cherry-pickers or lifts to serve as platforms for the artists, and they can consume a lot of paint. Gitler gives the artists wide latitude for depicting their chosen bird(s). The only requirement is that the piece be representational. While abstractions or swaths of color might be interesting art, only murals that look like a bird are allowed. Accordingly, some artists choose to present their bird realistically, painting the shape and coloration of the bird fairly accurately. Other artists may depict the bird’s form accurately, but not its color. Some artists go for a cartoon-like representation, while others tell a story by bringing in the bird’s habitat or diet. Bald Eagle, by Peter Davington Pinyon Jay, by Mary Lucy The mural project began with five murals painted in 2014 on the block that houses Gitler’s gallery. Currently the murals can be found from 134th Street on the south to 165th Street on the north and from Riverside Drive on the west to Edgecombe Avenue on the east. Most of the murals on drop-down gates are located on Broadway. Amsterdam Avenue has a fair number, and the side streets throughout the neighborhood have some “must see” murals as well. To find the most murals, you need to go birding when the gates are down—in the evenings or on Sundays. However, many murals are always on display on sides of buildings. Much like actual bird-watching, you never know which birds you’ll see. Some birds have been covered due to construction projects. One mural of a hummingbird, on a panel secured to a building, was stolen (it is reportedly being repainted). Yet other birds, newly painted, seem to suddenly appear as if blown in on the winds of a storm. Together We Rise, by ANJLNYC (depicting the yellow-billed magpie and American pelican) According to the staff at the gallery, local police have been impressed with the effect of the murals on the neighborhood. Not only have the murals drawn many “birders,” including families, to the area, but graffiti (that is, unauthorized street art) is on the decline. While tagging continues on unadorned surfaces, the murals themselves have not been tagged or defaced. Whether the murals will result in action to curtail or slow climate change is an open question, but it seems clear that the project has brought beauty and interest to this part of Upper Manhattan. Black-billed Magpie, by Andre Trenier The Audubon Society offers a tour of thirty murals on Sundays. Or, if you’d like me to share my favorite murals and give you a bit of history of the neighborhood as well, contact me for a custom tour ([email protected]). Townsend's Warbler, by ATM

On Saturday, May 5, we offered our tour Central Park: Marvels of the Northern Half as part of Jane's Walk, an international event in which people show off their favorite area of a city. We were pleased to have about 20 people select our tour from among 40 walks starting at the same time. We began with features of Central Park that many New Yorkers know, including a playground and the Reservoir. Then we took the group into lesser-known territory: the tranquil Pool and the North Woods. Everyone was amazed at the beauty of the area and how much it contrasts to the noise and grit of the city despite being smack dab in the middle of the city. Emerging from the woods, we saw the large body of water at the northeast corner of Central Park, the Harlem Meer. From the high bluffs overlooking the Meer, the group could clearly see the usefulness of the area for a string of fortifications during early American wars. Spring flowers accompanied us everywhere on this lovely May day, from the cherry blossoms along the Reservoir to the colorful tulips in Conservatory Garden, where the walk ended. The area is beautiful year-round, but it is truly a marvel in the spring. It's not too late to take a walk in New York's fabulous spring show in the northern part of Central Park. Join us for a repeat of this tour on Sunday, May 20, at 2 PM. We are offering it at a special price, $20 per person (a 20% discount from the usual price). Please sign up here, and we'll email you with the starting location.

Photos by Harvey Kopel. By Deborah Harley

With summer approaching, I’m looking forward to taking a nice relaxing ferry ride on one of the new ferry routes around NYC. Last year my husband and I cycled over to the Rockaways and afterwards ferried home -- sipping a beer and watching the scenery go by—all for the price of a subway ride, but a whole lot more fun. Ferries have become the trendy new alternative for getting around New York. The city has even added a new commuter ferry to Astoria, Queens. Which brings to mind a story that Robert Caro tells in his Pulitzer Prize-winning book The Power Broker, about the incorrigible Robert Moses, and a time when ferry service to Astoria wasn’t so prized. During the early twentieth century, a municipal ferry house stood at 92nd Street and York Avenue in Manhattan. The ferry, named the Rockaway, carried commuters between Manhattan and Astoria. In 1936, Mayor Fiorello La Guardia arranged to end the city-operated ferry and transfer the land to the Triborough Authority to build a new approach to the Triborough Bridge. La Guardia finalized the plans for the turnover on July 15 but gave the ferry an additional sixty days to wind down operations while ferry riders found alternative ways across the East River. However, Robert Moses, who headed the Triborough Authority, didn’t want to wait that long. Robert Moses, for those who don’t know, was for many decades the most powerful man in New York City and New York State. Arguably, he was even more powerful than Franklin Roosevelt, who was then President of the United States. Caro maintains that Moses was singularly responsible for the physical direction that the entire country took during the first half of the twentieth century. He influenced a generation of young urban engineers who went on to design and build the national landscape that we live in today. Moses was a man who was used to getting what he wanted. Not willing to wait for LaGuardia’s sixty days to pass, Moses took action to raze the ferry terminal immediately. On July 21, after the Rockaway had pulled away from the terminal for an early afternoon run, Moses directed his contractor to block access to the terminal both by land and by sea and to yank the slip apart. When Plants and Structures Commissioner Frederick Kracke heard what was happening, he frantically tried contacting La Guardia while he dispatched Deputy Commissioner Andrew Hudson to halt the destruction. Arriving at the scene, Hudson could not believe what was happening. The Rockaway was already on its return trip to Manhattan and would not be able to dock. Worse yet, in a few hours hundreds of commuters would suddenly find themselves stranded and unable to make it back across the river to their homes in Queens. Hudson argued with the contractors, whom Moses had instructed to stop at nothing, even as the dock was being torn to bits. La Guardia, meanwhile, was livid. He contacted Moses, begged him to stop the destruction, and promised to shorten the waiting period. When that didn’t work, he ordered the police to intervene. But the contractors knew who their boss was—and it wasn’t the mayor or the police. It was Moses. Rush hour came, and a steady stream of commuters stood on York Avenue watching helplessly as the ferry dock was being carted away. La Guardia pushed harder, and the police were finally able to stop the contractors from destroying the rest of the dock. That night, the city hastily rebuilt the damaged dock and ferry house. By morning, the Rockaway was back in service. In the end, Moses won the battle. La Guardia waited about a week for the story to play out in the papers and then quietly allowed the demolition to begin in earnest. Late on the night of July 31, the Rockaway pulled away from the terminal for the last time, and the ferry house was torn down. By Laurie Lewis At New York’s Tenement Museum (www.tenement.org), you don’t just look at exhibits; you become part of them. The museum founders purchased a tenement building, researched past tenants, and restored many of the apartments to look as they might have when particular families lived there. You can’t walk through the building alone; you must take a tour with a guide, known in the museum’s parlance as an educator. It’s an apt term, because you learn so much from the guide: about tenement life, about the family that occupied the apartment at a point in time, and about society then and parallels today. I’ve taken most of the tours the Tenement Museum offers, and each time I leave with a better understanding and feel for life in a period we usually learn about only through reading. You get a much deeper appreciation from being in the very rooms that housed thousands of immigrants over the years—millions, when you consider all the people who lived in tenement apartments like the ones you see at the museum. Recognizing that words fall short of the experience of visiting a tenement, I’ll nonetheless try to capture some of the impressions from the tour I took recently of an Irish family’s home. The tenement building we visited is 97 Orchard Street, on the Lower East Side. Built in 1863, the building is one of the oldest tenements still standing. The Irish Outsiders tour focuses on the Moore family, who lived in the building for only a year, in 1869. Except for one other Irish family, all the occupants of the building at the time were German (which explains, in part, the name of the tour). Later tenants included Italians and East European Jews. We entered the tenement in a way you never want to enter someone’s home: through the back yard, a small plot with four privies. Standing in the little yard on a blustery March day, we didn’t have to think long about the challenges of answering the call of nature in inclement weather. Or the long flight down and the even harder ascent that Bridget Moore had to make to her fourth-floor home carrying sloshing buckets from the building’s only water source, near the toilets. For those who needed a little help imagining the burden, the museum has filled a pail with stones to approximate the weight of water. The educator, Sara, pointed out that Bridget probably carried two pails at a time, one in each hand, to avoid another trip, although she might have had difficulty doing that with three young children along. Bridget and Joseph Moore lived in a three-room apartment with their three daughters, the youngest an infant. The layout of their apartment was similar to that of all apartments in the building, indeed in most tenements. The living room of the Moore’s apartment faced the street; the living room of the back apartments overlooked the privy yard. A bedroom could hold a double bed and dresser but not much else. Between the living room and the bedroom was the kitchen. The stove was the only source of heat in the apartment. Although we saw fireplaces, they were too shallow to be functional, Sara explained, and were boarded up almost as soon as the tenement was built. The museum limits the size of tour groups. The twelve people in my group filled each of the small rooms, even the unfurnished rooms we saw in apartments that the museum has not restored. “Cozy” doesn’t begin to describe the feel. Previously, I had toured the restored apartment of a Jewish family that had lived in the building about thirty-five years after the Moores. The entire family, even the children, did piecework for the garment industry, and they were often joined in their home-based sweatshop by other workers. The apartment struck me as too dark to do delicate sewing, and I perspired just thinking about the heat in the airless space on a summer day with all those bodies and an iron going full blast to press the clothing under construction. Tenements like this were the first homes for most immigrants in New York through the early twentieth century. Although some people moved out as soon as they were able, others lived in these conditions for many years, and second-generation tenement families were not uncommon. It’s hard for modern-day Americans to appreciate what our ancestors endured, what was considered normal for the working class. A visit to the Tenement Museum is a great eye-opener. For more about tenements in New York, see our April 2018 newsletter. |