|

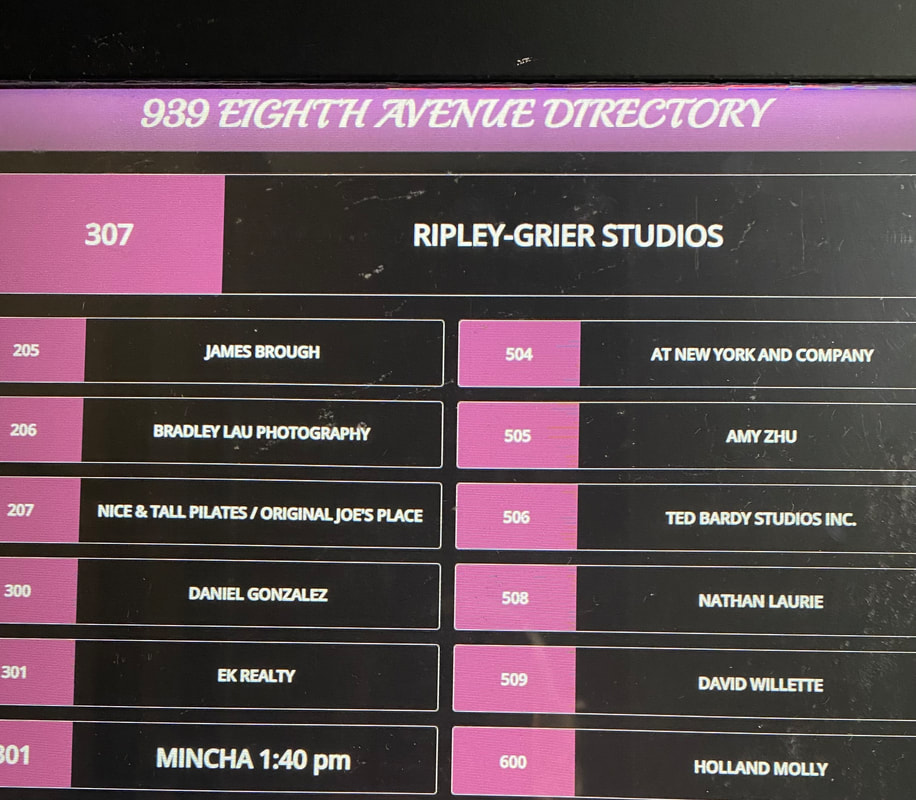

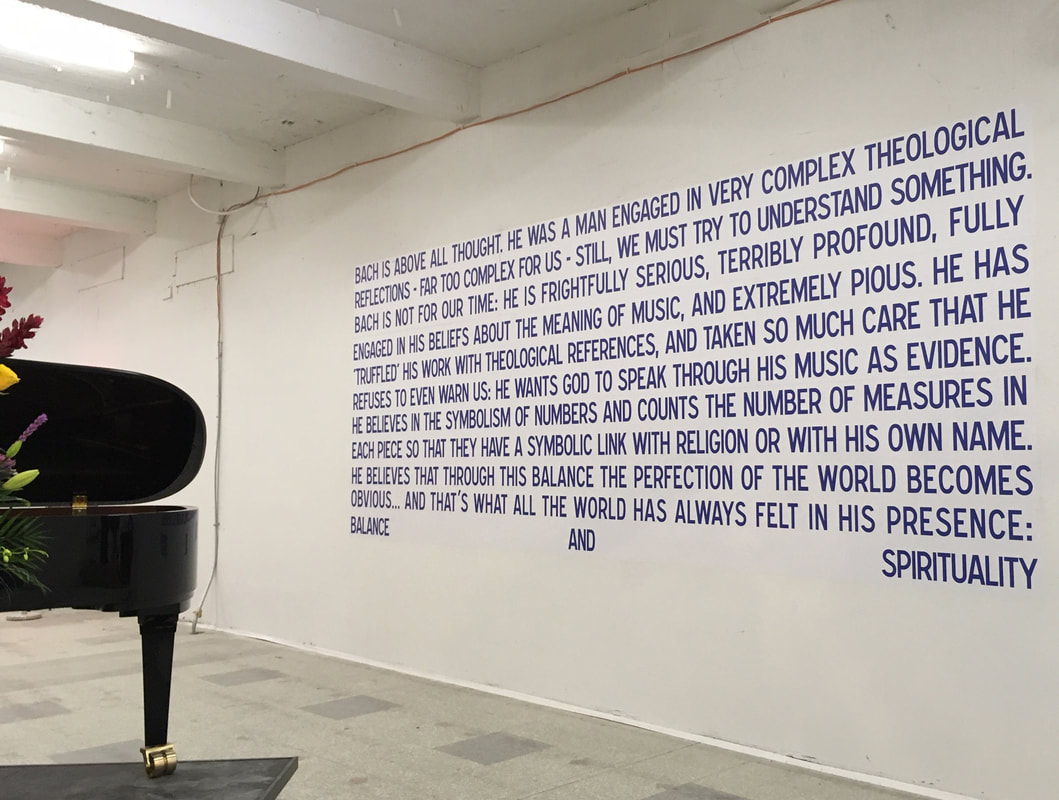

By Laurie Lewis I had an interesting experience this weekend when I went to check out 939 Eighth Avenue, the address that several sources give as the first Pilates studio in America. I was standing outside the building taking a photo when a young man held the door open for me. “Coming in?” he asked. I explained that I was just trying to get a picture of the directory. He asked if I was interested in the Pilates studio and told me he was the new director. The man introduced himself as Konstantin and invited me to see the second-floor studio, now operating under the name Nice & Tall. He explained that Joseph Pilates and his wife Clara not only had a studio here; it was also their home. Konstantin said that Pilates may have had a studio elsewhere in Manhattan before this one. But without doubt New York City was the location of the first Pilates studio in America. As you can see from the above picture of the the door to the studio, Joe Pilates set up shop almost a century ago. The German immigrant had already developed a methodology and some equipment to promote his philosophy of whole-body health, and he continued to hone his techniques and teach his approach over the subsequent decades. Boldface names in dance—George Balanchine, Martha Graham, Ruth St. Denis, and Ted Shawn, among others—were among Joe Pilates’ most ardent customers. They praised not just the physical conditioning but also the emphasis on mind-body control. In fact, Pilates called his approach “controlology.” Only after his death in 1967 at the age of 83 did his name become synonymous with his method. Clara Pilates and early disciples kept the methodology alive after Joe’s death. The technique also evolved to reflect modern-day understanding of how the mind and body work. Konstantin, the present owner of the Eighth Avenue studio, says his establishment emphasizes the classical approach but embraces the modern as well. Although the studio no longer has any of the original apparatus, it is filled with equipment based on Pilates’ design but enhanced with up-to-date touches. In part because of its reliance on specialized equipment and trained instructors, Pilates was slow to catch on. But it has withstood the test of time. Almost a century after Joseph Pilates opened the first Pilates studio in the United States, more than nine million Americans engage in the practice. This blog also appeared on www.nycfirsts.com, the website for Laurie Lewis's book New York City Firsts: Big Apple Innovations That Changed the Nation and the World. By Laurie Lewis The main reason I went to the Lower East Side in the past twenty years or so was to go to the Tenement Museum (see our April 1, 2018, blog A Visit to a Tenement). Of course, being a dedicated walker, I usually stroll around a neighborhood I’m visiting, and I have noticed how much this area has changed over the years. It used to be rather sketchy, but recently it’s felt safer and more vibrant. Now, with the opening of Essex Market, the Lower East Side has become a destination for New Yorkers and possibly for tourists too. Essex Market is an upscale replacement for the Essex Street Market across Delancey Street. That indoor market, which opened in 1940, was a replacement for the open-air pushcart market that clogged the already congested streets of the Lower East Side in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Many of the old structures in this area have come down, and in their place a multi-building, mixed-use development called Essex Crossing is rising. I won't comment on gentrification. I'll simply say that Essex Crossing will fill the neighborhood again with residences and businesses, starting with the food shops of Essex Market. I visited Essex Market twice in recent weeks. The first time—my initial visit since the market opened last May—was on a weekend. The building was mobbed with browsers, shoppers, and eaters. I left quickly, planning to return on a weekday. Sure enough, when I went back on a Thursday afternoon, Essex Market was a different scene. I arrived around 1:30, anticipating that it might still be a bit crowded at the end of New York lunchtime. But the Lower East Side is, for now, a weekend and evening destination; it has not yet become a major business district. The specialty shops on the entry level of Essex Market feature all sorts of food, some ready-to-eat, some requiring cooking. Several groceries the size of bodegas also offer a variety of foods for neighborhood residents to cook or eat at home. On the lower level is a food court of sorts—it has numerous purveyors but no central seating area; customers can sit in several alcoves or take their food to the mezzanine above the shops or carry it out. Both the shops and eateries feature foods of many ethnicities (lots of Asian cuisines), dietary preferences (quite a few vegan choices), and prices (generally moderate, although I enjoyed shopping at a bargain-priced bodega). One thing disappointed me. In this formerly Jewish neighborhood, I saw many pork products but no pastrami or blintzes. By Laurie Lewis Many New York neighborhoods have their local celebrities. On the far eastern avenue of the Upper East Side that gives the Yorkville neighborhood its name, the celebrities have webbed feet and quack. For the past six springs, a pair of mallards have taken up temporary residence at the pools in front of two York Avenue apartment buildings. My first sighting of the Duck of York this year was on Sunday, April 14. The male, the more colorful of the pair, was alone. I asked the doorman if the female was around, and he said he hadn’t seen her for a while. Now I want to make a disclaimer. Rumor and hearsay rather than solid evidence are the fodder of celebrity reporting. What I did not witness myself in my brief visits to Duckville every few days I heard from the staff of the apartment buildings and the neighborhood residents who, like me, had added duck-checks to their regular routines. As with any celebrity sighting, the facts may have been distorted, embellished, or only partly reported. It turns out there was a reason for the apparent disappearance of the female duck. She was tending to her nest in the bushes by the pool in front of the apartment building across 73rd Street. The ducklings hatched around April 21—how appropriate: Easter! I first saw the ducklings on April 25. Thirteen adorable little balls of yellow and brown fur! The doorman told me they had mostly been staying under Mama. But this was a nice day, and they were enjoying the sun. Four days later, the young ones had become expert swimmers. Most of them stayed close to Mama, but a few ventured out on their own. That daredevil tendency would soon cause problems. I asked the doormen and neighborhood duck-watchers if the father ever helped with the babies. I always got the same sort of reply: “Are you kidding? He’s a guy! Guys don’t help with the kids.” Twice I heard about a time soon after the ducklings hatched when Daddy Duck flew over from his solitary pond across the street. As soon as he touched down, Mama took off. As one storyteller said, “It’s hard being a single parent. She needed a break.” But Daddy didn’t pay any attention to the babies, spending Mama’s entire 15-minute break preening himself on the other side of the pool. When the ducklings were almost two weeks old, I counted only 10 babies. Then I started to hear stories about the adventurers, not yet able to fly, who hopped off the ledge around the pool onto the circular driveway. Danger! And not just from cars. The doorman told me that one youngster waddled too far, despite Mama’s attempt to lead him back to safety, and fell through a grate. A staff member lifted the grate, extended a ladder into the deep hole, and climbed down to retrieve what he was certain would be a dead duck. To everyone’s amazement, the duckling was alive. Life in a concrete city is not ideal for ducklings. On May 8, the surviving babies (8? 9? 10?—I heard each of these numbers) were taken to a new home, a farm on Long Island. There they would receive proper care in an environment better suited to little duckies. I heard about this from a friend, who reported that Mama Duck was hysterically hunting for her babies. I went to check on her. When I arrived at the ducks’ home, I was startled to see a new, colorful duck. Neighborhood duck-watchers identified him as a wood duck. They also told me that somebody was going to take Mama to her babies the next day. But the next day, the three adults—Daddy Duck, Mama Duck, and the wood duck—were still there. The newcomer was trying to fit in, but Daddy Duck would have none of that. Apparently, he and Mama are long-term partners. Daddy was willing to share her with babies, but not with another adult male. Mama continued to look for her young for several days. Once, when I was talking to the doorman, she came right up to us, as if asking for help. The doorman said she had been doing that ever since she lost her young. Several days of nonstop rain kept me away from the ducks. When I finally made my next pilgrimage, Daddy and Mama were alone, sleeping. The wood duck was nowhere in sight. A building employee said he hadn’t been around for a few days. I asked why they didn’t take the parents with the babies. The worker told me that they had done that a previous year, when the ducklings were transported to the same farm. But the adults flew back within a few hours. This, after all, is their springtime home. by Deborah Harley Ever have a New York Moment? I bet you have if you have spent any amount of time in this city. A New York Moment can be many things. It is usually serendipitous, surprising, and always memorable. A New York Moment is wonderfully intimate, fusing a connection between the city and its people. I have had many New York Moments, and I love to give others theirs. For example, a while back, my husband Bill and I were hosts to two members of his extended family – Rob and his 14-year-old daughter Kayla. They had traveled in from a small town in Eastern Pennsylvania to see a Yankees games – a birthday gift to his daughter. Bill and I gave them a whirlwind tour of Manhattan before chauffeuring them on the subway to their afternoon game in the Bronx. As we jostled through Midtown, I kept hoping to find that special something that would make their trip really memorable. Afterwards, we met again in front of the stadium and escorted them on round two of Manhattan. It was already dark as we strolled through Bryant Park and up Broadway to show them the spectacular, albeit gaudy, lights of Times Square. Midway through the chaos I suddenly realized that we were about to encounter a situation that demanded my immediate intervention. With an audible “Oh s___!”, I abruptly turned to Rob and deadpanned hastily, “Oh, by the way, before we go any further, I need to tell you that it is perfectly legal for women to go topless in New York City.” “Who? What?” Rob crumpled his forehead. Why would I even mention such a thing at that particular moment? But as I stepped aside, Rob’s baffled look transformed into a gaping, wide-eyed, and embarrassed stare as he found himself face to face with a buxom young woman with blue-painted breasts. Noticing the shock that was engulfing him, I quickly managed to whisk everyone away from the craziness. But I have to admit, as we made our escape through the crowd, I found myself sporting a satisfied smile. Rob had experienced his New York Moment. But that’s not the only New York Moment that I want to tell. That came as a result of reading an article in The New York Times about Evan Shinners, a young Julliard-trained pianist who was on a spiritual quest to better understand the music of Johann Sebastian Bach. To accomplish this, he decided to spend a month playing marathon sessions of Bach in a rented public venue. The very next day, as I desperately sought shelter from a cold, rain-drenched afternoon, I found him. The storefront room was large, clean, and starkly white, surrounded on two sides by floor-to-ceiling windows. “Come in and listen,” the sidewalk sign beckoned. A red neon “Bach” glowed in the window behind it. The room was empty except for a scattering of folding chairs and stubby stools on one side of a baby grand. On the other side were two harpsichords and an extended quote printed in large, blue, block letters referencing a rejection letter that Shinners had received from Pierre Hantaï, a French harpsichordist and notable Bach interpreter. Shinners had hoped to study under him; however, Mr. Hantaï had dismissed Shinners efforts and expressed concern that he lacked the spirituality that Hantaï felt was essential for performing and appreciating Bach’s work. Thus, Shinners would be forced to face the quote daily as he sought to elevate himself spiritually.

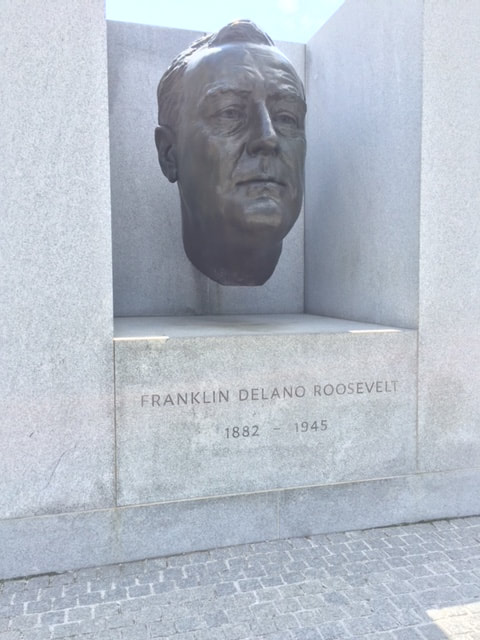

I was so enchanted by the intimate setting that I told my husband about it. That Saturday, Bill and I headed to W 56th St & Broadway. Because it was lunch time, we picked up some soup nearby to enjoy while listening to Bach. However, instead of Shinners on the piano, we were first greeted by a performance of a young violinist -- playing Bach, of course. More audience members wandered in while we finished our lunch and sipped our complimentary coffee. My husband sat astounded by the experience. Where else but in New York could you stumble across such a thing and right off the street: a spiritual journey attainable only through the sharing of it with strangers. It got me thinking: New York has so much freely available for everyone to enjoy. All you need to do is step outside your door. It’s only then that you’ll truly experience this wonderful city. By the end of our lunch I had realized that Bill had found his New York moment. By Laurie Lewis Franklin D. Roosevelt Four Freedoms Park opened in 2012 at the southern tip of Roosevelt Island, a narrow strip of land in the East River between Manhattan and Queens. The park is situated on a four-acre triangular plot of landfill. Renowned architect Louis I. Kahn envisioned this memorial shortly before his death in 1974. A row of five copper beech trees separates the landmarked ruins of the Smallpox Hospital, designed in 1854 by James Renwick, Jr. (architect of St. Patrick’s Cathedral), from a white granite staircase leading to the FDR memorial. The view from the top of the stairs is spectacular: the Midtown Manhattan skyline to the right, Queens to the left, and a wedge-shaped lawn lined on each side by sixty little-leaf linden trees. The tapering lawn points to the centerpiece of the memorial. A larger-than-life head of Franklin Delano Roosevelt greets the visitor. Enlarged from a bust that sculptor Jo Davidson made of the President in 1933, this bronze head is six feet tall and weighs 1,050 pounds. Granite slabs behind the FDR image contain words from his eighth State of the Union address, known as the Four Freedoms speech. The President spoke of what every place in the world needs: freedom of speech and expression, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear. More granite slabs create walls perpendicular to the stones engraved with the excerpt from the Four Freedoms speech. Architect Kahn called this granite rectangle the “Room.” The Room is open at the south end and on top—perhaps suggesting a world open to possibilities? I have been to the Four Freedoms Park several times. Each time, I have been amazed by the serenity; even on weekends, it is not crowded. The most impressive aspect is the view, especially of Manhattan from a perspective that otherwise can be obtained only from the Queens side of the East River. The United Nations is directly opposite the Room, and iconic New York structures like the Chrysler and Empire State buildings peek out from the background. Yet as magnificent as the views are, the Four Freedoms Park lacks something, in my opinion. Perhaps it is a matter of semantics. To me, a park must be green. Aside from the tree-lined lawn, this is predominantly a white stone place. In a park, the eye should be drawn to its elements—not away to scenery beyond its borders. A park should entice visitors to relax and linger. Little seating is available for this purpose, except for flat granite slabs in the Room; the lawn and shady border lack benches. Perhaps this is why the park has so few visitors compared with more perfect retreats like Central Park and Bryant Park. Even if Roosevelt Island’s Four Freedoms were considered a memorial rather than a park, it falls short of the FDR memorial in Washington, DC. That structure tells multiple stories, with many quotes and statues. The Roosevelt Island tribute to the four-term President is an example, as I see it, of less not being more. To learn the history of Roosevelt Island and how it is eco-friendly, see the September 2018 newsletter.

|